Life and Limb with Connor

Meet Connor Talbot. The animal-loving, electrical engineering grad. He co-founded, ProstheteX, to eliminate human prosthetic pain with data centric solutions!

We caught up with Connor in an exclusive interview.

Here’s what he shared with us!

1. It’s interesting to note how as an electrical engineering graduate, you got to work with animals and then transitioned to working with humans in the area of prosthetics including data centric solutioning. How did this come to be?

“I started dog walking during a university break and discovered my love of animals, eventually leading to me working at an animal rehabilitation centre in my home country, looking after injured farm animals."

“I came across injuries in these animals that often lead to full limb amputations or euthanisation. This got me thinking of partial limb amputations instead as a less traumatic approach to rehabilitation, naturally in combination with a prosthetic to replace the lost limb function."

“I turned this into a final year university project and discovered my work partner who worked part time as a prosthetic technician. Through further research and amputee interviews together it became apparent the fit of prosthetics in humans was a greater issue.”

2. How is it that prosthetic sockets are ill fitting? And how does Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) work in addressing this?

“The fitting process consists of creating a positive plaster mould of the patient’s limb in a static position, then creating a rigid shaped socket, however the limb itself is highly dynamic constantly changing shape due to fluid retention and weight changes."

“Additional challenges occur as all amputations are different, the skin is incredibly complex, many amputees suffer comorbidities such as diabetes, and the final fit of the socket is dependent on the skill of the prosthetist. "

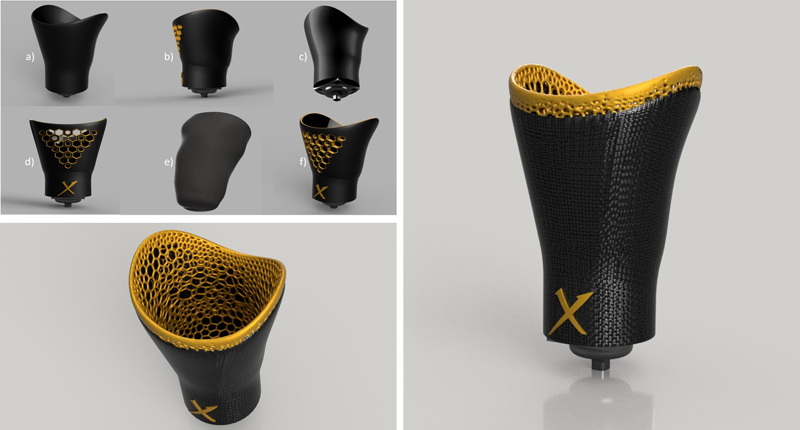

“SLS in combination with a 3D scanning technique may allow a more accurate model of the limb to be created, under many different loading scenarios, leading to a better-informed socket design. We have found that SLS printing does have many limitations however in its current state.”

3. Data centric solutioning. Can you explain that in this context – What does that mean and how does the vital limb information get captured?

“We were investigating a different approach to the problem, rather than manufacturing sockets, moving towards a diagnostic liner of sorts. A liner that can detect shear pressures and pressure on the limb. Using this data to inform prosthetists of problem areas which they can then work to fix.”

4. Has this been trialled? If so, what do patients think about better fitting prosthetics that were produced and informed by the new ways of capturing vital data on their limbs?

“We have manufactured sockets but as of yet have not trialled with patients, as we have run into difficulties concerning the strength and flexibility of the prints, so more work needs to be done and other modes of manufacturing are being considered.”

5. What are things that stand in the way of wider acceptance and use of SLS in informing such prosthetic work? What do you see yourself focusing on next?

“For starters from our experience we don’t think SLS in its current state is suitable for weight bearing i.e. in lower limb amputees, however, could find some use in upper extremity amputations. From our testing our focus is shifting more towards systems for measuring and tracking limb variables to inform better socket design.”

.jpg)

d1-01.jpg)